Using magazines, advertising, cinema, and vernacular imagery as primary subjects of inquiry, Barrois’ multimedia practice breaks down and re-configures the language of print, design, and popular culture in order to investigate underlying ideology, ethics, and conceptions of identity. Barrois’ current work deconstructs, re-frames, and re-presents the images, graphics, and language of advertisements from National Geographic Magazine issues of the 1970s and 1980s, and the 1988 Soeul Olympics. This series exposes the underlying language of the promise of technology and the construction of desire for consumers to know and conquer the world, all while somehow protecting the fate of the planet.In various ways, Barrois navigates questions around color, control, taste, waste, and the layering of information. He is half of LAB:D, with artist Addoley Dzegede, and he is a new Assistant Professor of Art at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, PA.

Exhibitions

Others Who Struggle with Nature

November 18, 2020 to January 31, 2021

Others Who Struggle with Nature features new work by Lyndon Barrois Jr. in his first New York solo presentation. Among shifts and changes in the artist’s practice, as well as relocation(s) and loss of materials due to the conditions of the pandemic, he has returned the context of sport and spectatorship, relative to branding, image production, individual identity, and collective behavior.

It began with a National Geographic ad from 1989 advertising Goldstar as the media and technology sponsor of the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul. The ad was the seed reference for this project, and the start of Barrois Jr.’s interest in the 88’ Seoul Olympics, specifically. The games were an opportunity for many Korean companies—from technology to apparel—to exhibit their offerings to the world, and promote an image of progress and modernity, in attempts to dissolve a predominantly povertous reputation. The hosting of the games also allowed South Korea to establish diplomatic relations with otherwise adversarial governments, and considered by some to be the unofficial bookend of the Cold War.

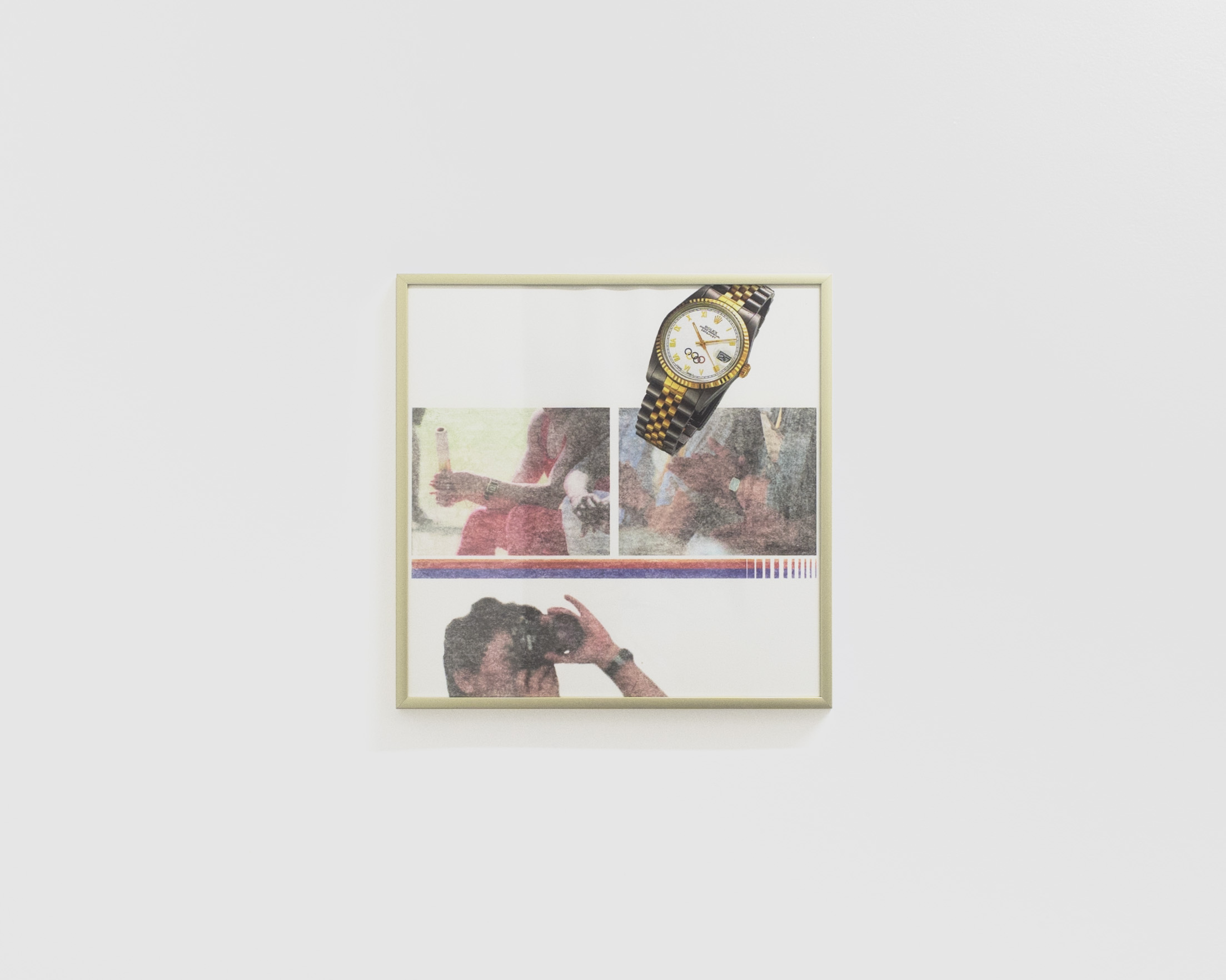

The exhibition builds on a consistent interest in locating parallels and contradictions between the featured content and broader culture. While the Olympics has historically brough nations together under the guise of global unity, it is worth remembering that many of the events, while peaceful in their modern iterations, were designed to display militaristic skillsets, and wartime abilities. Likewise, there is a circular relationship between rifles, cameras and timepieces, which all depend on their assets as precision instruments that mark time and distance.

The title of the exhibition is taken from a title segment in the film Hand in Hand (Im Kwon-taek, 1989) following a segment on doping throughout the competitions. Those other athletes who ‘struggle with nature’ are ones opting to not cheat the process; ultimately physical competition is a war with the elements, our bodies, and the natural laws of physics. The phrase also opens up other questions around human nature, and the so-called ‘natural order of things’ in many social, commercial, and political contexts that we continue to struggle with in an evolving and re-volving manner with every generation.

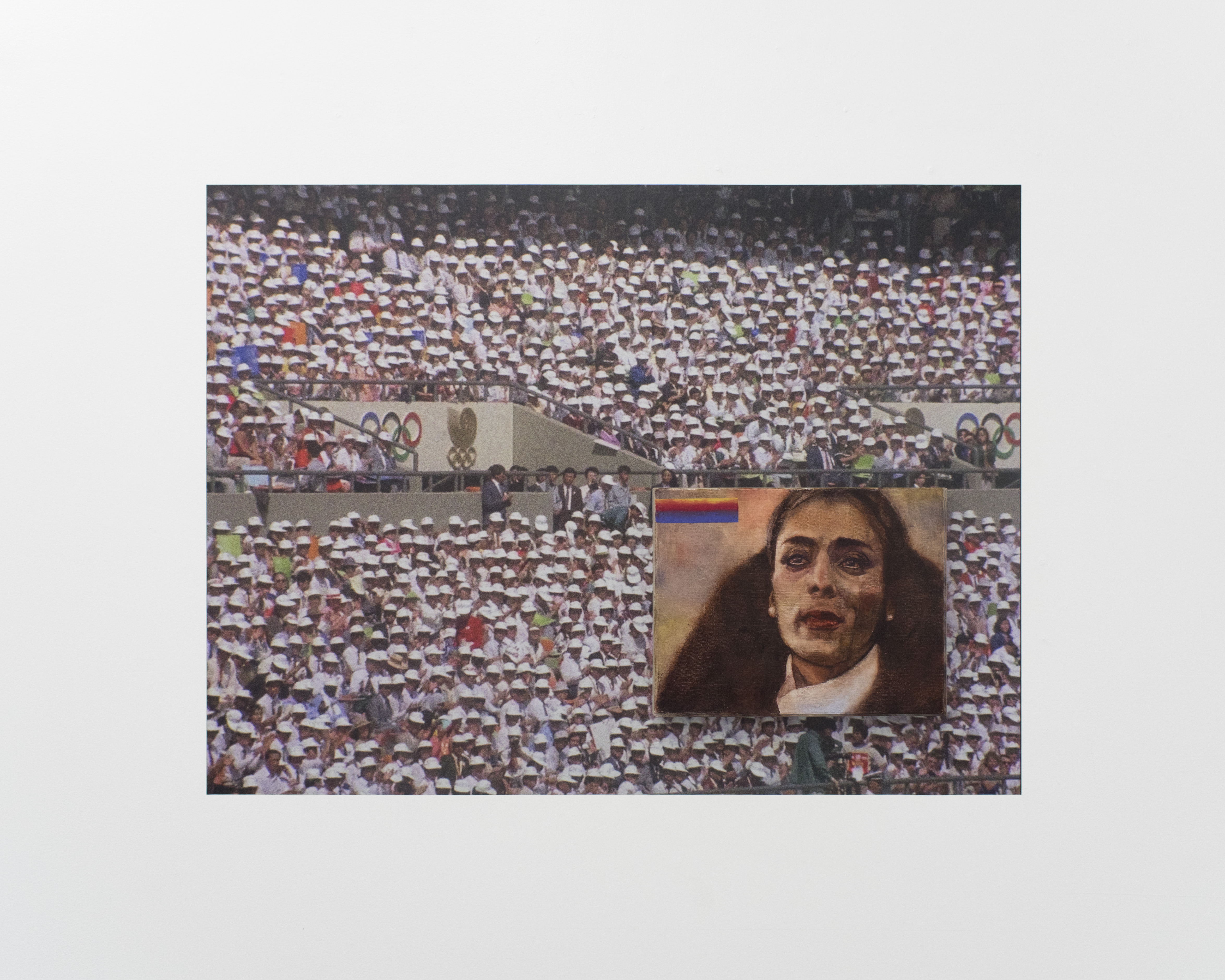

Perhaps most recognizable is the likeness of Florence Griffith-Joyner, who won three gold medals and one silver in Seoul, setting Olympic and world records in the 100m and 200m sprint, respectively. The month prior, she set the world record for the 100m in Indianapolis, and these records still stand today. Often publicised for her fashion sense, it was reported that she spent more time each day on her nails and makeup than it took to complete the total 14 minutes of her event participation. Barrois Jr. is interested in this not as critique, but rather her recognizing the importance of image and self-presentation on a global stage. She also shattered the assumption that you cannot match fashion with exceptional performance. She has emerged as the only recurring figure throughout the exhibition.

The work shown consists of themed groupings and compositions forming relationships between collected film stills and ephemera from the event and time period. The three films being referenced are Hand in Hand (Im Kwon-taek), Beyond Barriers (Lee Ji-won), and Seoul 1988 (Lee Kwang-Soo), all produced in 1989 to examine the games through different lenses. Each of these films present unique commentaries on the event, taking separate interests in particular sporting events, highlighting the spectacle of the opening and closing ceremonies, the political history of the Korean peninsula relative to other participating nations, and the militaristic undertones of Olympic competition. Barrois Jr. is intrigued by each of these perspectives, as well as the literal capturing of it all. At the heart of it all, there are many pictures of people taking pictures.

Camera as Weapon: Military Values in the 1988 Seoul Olympics

Essay by Eunice Uhm

Just a year after Ronald Reagan proposed the Strategic Defense Initiative in 1983 (also known as Star Wars), Paul Virilio published War and Cinema (1984). In this influential book, he examines the close relationship between war and cinema, as he writes, “For men at war, the function of the weapon is the function of the eye.” Addressing the ways in which cinema is materially connected to war in a period of advanced radar systems, satellite imagery, and smart missiles, Virilio argues that the technologies of military and cinema become increasingly intertwined. He states, “The Americans prepared future operations in the Pacific by sending in film-makers who were supposed to look as though they were on a location-finding mission, taking aerial views for future film production.” The technology of cinema, or more specifically the camera’s ability to capture, not only articulates and adheres to military technology, but also transforms the world into, in Rey Chow’s word, a target.

It is within this charged context of technology, implicated in the politics of militarism and imperialism, from which I engage with the images of the 1988 Seoul Olympics. The Seoul Olympics marks a watershed moment in Korean history. After over three decades of Japanese colonial domination (1910-1945), the Korean War (1950-1953), the military coup d’état of Park Chung-hee (1961), and the dictatorship period from Park Chung-hee to Chun Doo-hwan (1961-88), the Seoul Olympics took place during a turbulent period of social reforms for democratization in South Korea. Simultaneously, it signaled the shifting political and economic landscape in Korea – a turn towards globalization. With the increasing liberalization of economic and political policies (that include but are not limited to the relaxation of citizens’ overseas travels and the importation of foreign goods), the 1988 Olympics became an international platform where South Korea established and presented its new national identity. In other words, the Seoul Olympics became a spectacle that captured, in Youjeong Oh’s words, “the gaze of foreigners.” My line of inquiry emerges from the dynamic ways that a new Korea was documented – or captured - during the 1988 Olympic Games: what exactly was captured? Who captured it? And what were the political implications of this “capture?”

The opening ceremony for the Seoul Olympics demonstrates an impressive synchronized movement of masses of people. The camera oscillates between the aerial view and the ground view, contrasting the seamlessly synchronized choreography and the rigorous and rapid movement of individuals who perform it. Along with the theme song of the 1988 Olympics performed by singing group Koreana, Hand in Hand, the aerial view of the mass is intended to evoke a sense of harmony, a word that is literally visualized by the crowd that holds up differently colored paper to create each letter of the word (Indeed, the motto of the 1988 Seoul Olympics was Harmony and Progress). Despite Korea's attempt to promote a theme of harmony, Western reception highlights the dynamics of power within the racializing foreigner's gaze, exposing the impossibility of the Olympic institution's expressed ideals of multiculturalism. In a Rolling Stone article “Seoul Brothers,” P.J. O’Rourke writes about “pie-plate” faces, “identical anthracite eyes,” and Kimchi breath that could “clean your oven.” In an article, “Jingo Olympics,” published by the New York Review of Books, Ian Buruma compares the 1988 games to those Hitler sponsored in 1936, as he writes that Korea is “one of the few countries that combine capitalist economy with the militant patriotism and obsession with folk culture more often seen in Communist states.”

The hostile, if not blatantly racist, comments made by the West (more specifically the United States) allude to the lingering tension and anxieties of the Cold War, an asymmetric partnership in which Korea serves as a ground for the US to enact its imperialist (disguised as anticommunist) fight in exchange for economic and military support. Along with his comment on “[Korea’s] militant patriotism […] often seen in Communist states,” Buruma further wrote of a government spokesman who privately criticized the “crass attitude of Americans” and their insensitivity towards Korean culture, comparing it against German viewers who “understood the symbolic depth” of the opening ceremony. In response, Buruma proclaims, “Well, I thought with an element of spite: they would, wouldn’t they.” Buruma’s implicit (perhaps explicit?) categorization of the synchronized movement seen in the opening ceremony as “Communist” registers sharply with the ideologies of the Cold War, in which the notion of American individualism triumphs over the communist collective. (It should also be noted that the binary of individualism and collective is highly racialized, as it often aligns the Western culture with individualism and the Eastern culture with collaboration.)

In consideration of this contentious and precarious political position of South Korea in the global world in the 1980s, the 1988 Olympics becomes, then, a site that articulates the dis-harmonious structures of power, charged with the geopolitics of race and nation-state. In other words, the aerial views that capture the opening ceremony can be understood not simply as a form of entertainment, but as a sight/site of power struggle, one where military technology surveys and evaluates its target, South Korea.

The inherent nature of the Olympics, indeed, echoes the logic of war. Its supposedly “friendly” competitions not only evoke but also demand a sense of patriotism, reinforcing the boundaries of nation-state. And perhaps more importantly, it celebrates the same set of skills and abilities that is often expected of soldiers at war. For example, Kim Soo-nyung (South Korea) won an individual and team gold medal in archery at the 1988 Olympics. Her nickname, “Viper,” suggests her abilities as an archer to attack precisely, aggressively, and dangerously. In a picture of Kim Soo-nyung, her attention is focused as she aims for the target. Positioned on the foreground, she becomes the focus of our attention even as the viewer is denied a frontal view. The clear and sharp image of her form contrasts the blurred image of a target in the background, allowing the viewer to visually target her just as she aims at her target. With her back straight and her right arm stretched out back, the Korean flag logo on her jacket clearly marks her national identity and association. The prominent Korean flag logo, along with a profile view that hinges on her back, deindividualizes her, constructing her as a representative of South Korea who metaphorically and literally shoots for her country.

The photograph of Kim Soo-nyung illustrates how the rhetoric of the military unfolds in the Olympics in two distinct ways: 1) the value placed on a set of militaristic skills in sport; 2) the photographic technology that captures the event. In consideration of the inherently militaristic nature of the Olympics, one must question, then, the ways in which Korea’s (re)presentation of its military prowess was harshly criticized and categorized as “Communist.” The synchronized movement shown in the opening ceremony for the Seoul Olympics parallels more closely to the language of the military, and less to the characteristics of Communism. Why was Korea’s “militant patriotism,” a value that the Olympic institution demands and celebrates, perceived as a source of contention and anxiety? How can Korea’s exhibition of “militant patriotism” be understood in the context of the inherently militaristic nature of the Olympics? Subsequently, can it be understood as a defensive (and even perhaps appropriate) response to camera technology that captures South Korea (or in Chow’s word, a target)? Despite its disguise as a harmonious international sporting event, the 1988 Seoul Olympics stands as an allegory that exposes the contentious geopolitics of nationhood. After all, the value and technology of the military is much more intimately embraced than anyone would like to admit.

Bio

Eunice Uhm is a PhD candidate who studies modern and contemporary art, with a transnational focus on the United States and East Asia. Her dissertation examines the conditions of migration and the diasporic subjectivities in the works of contemporary Japanese and South Korean art from the 1960s to the present.

1 Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception (1984), trans by Patrick Camiller (New York and London: Verson, 1989), 20.

2 Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine (1988), trans by Julie Rose (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994), 49.

3 Rey Chow, The Age of the World Target: Self-Referentiality in War, Theory, and Comparative Work (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006).

4 In Pop City: Korean Popular Culture and the Selling of Place (2018), Youjeong Oh writes, “the gaze of the foreigners has been a persistent theme in South Korean development. In pursuing export-oriented economic development, the developmental state cultivated a mentality of consciousness of the foreign gaze: an outlook that emphasizes the extent to which the international community is paying attention to the performance of South Korea, a postcolonial latecomer on the world stage. To verify the extent of this gaze, domestic media have competed with one another to deliver overseas responses to major sporting events such as the Seoul Olympic Games in 1988 and the Korea-Japan World Cup in 2002.”

5 P.J. O’Rourke, “Seoul Brothers,” Rolling Stone, (Oct. 1988).

6 Ian Buruma, “Jingo Olympics,” New York Review of Books, (Nov. 10, 1988).

7 Buruma, “Jingo Olympics, 1998